In case it was not already obvious, we are back to reading The Cantos

Apparently, this is actually the beginning of the Pisan Cantos. I don’t know what the other section was. Just that it was… short.

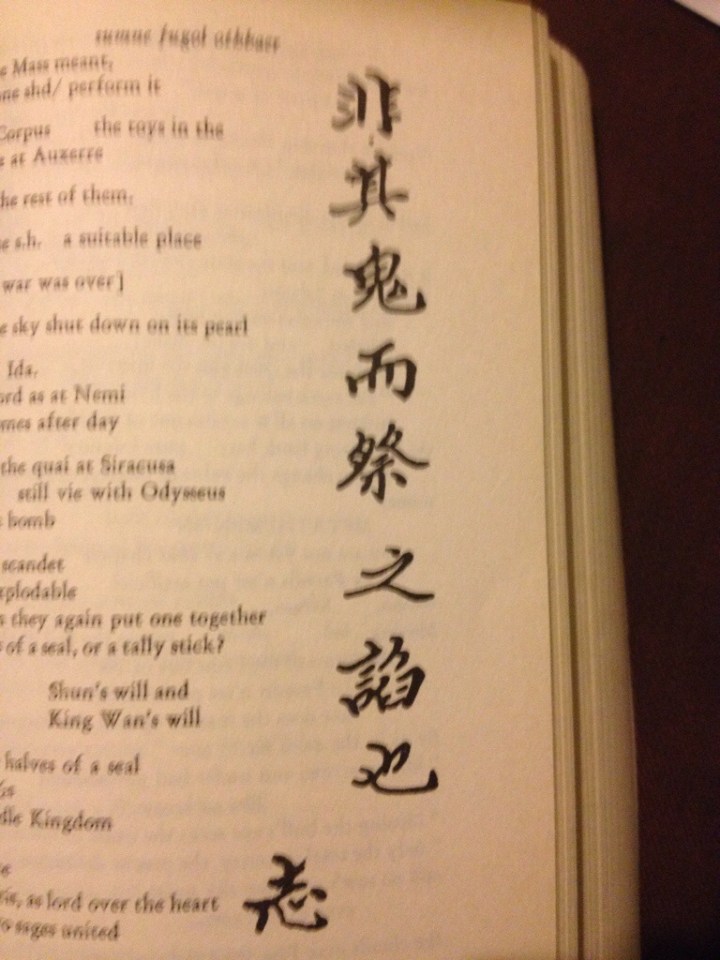

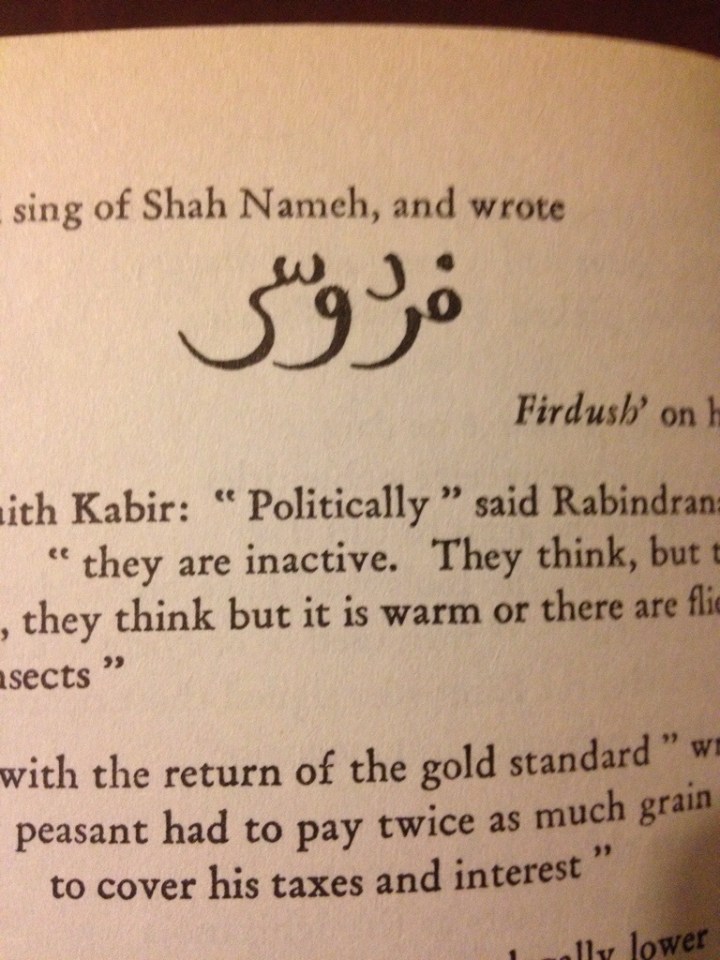

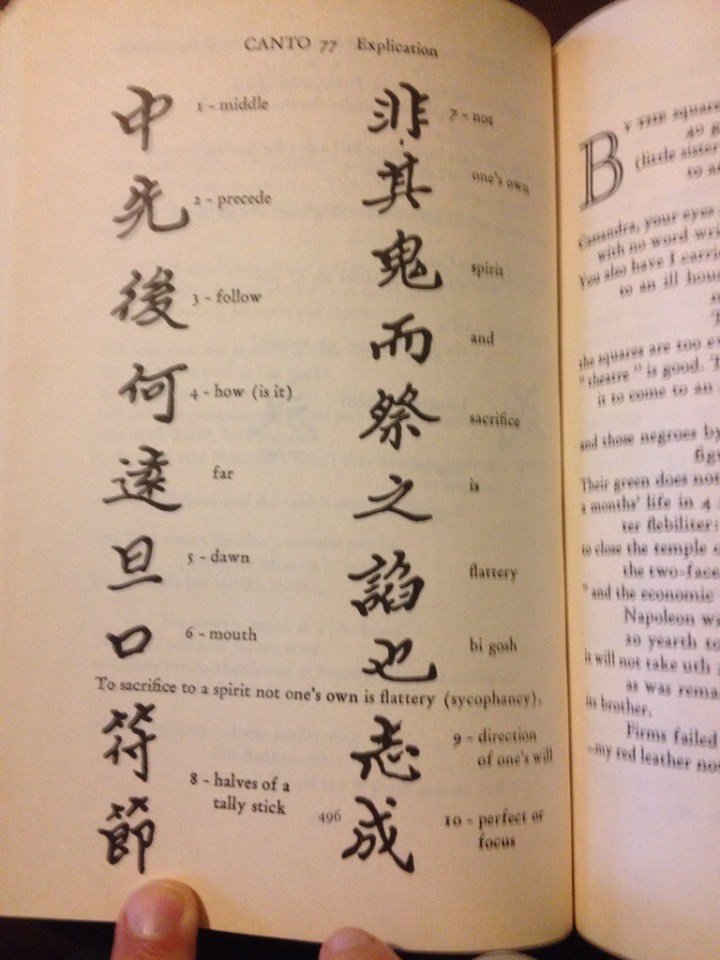

The themes remain (Chinese characters, finance, anti-communism, anti-semitism, Italian history), but the style has changed. Not radically, but noticeably.

There’s a reference to Hemingway, which may not seem like much, by this adds a bit of autobiography that I didn’t notice before, and that’s not a small thing. Also, I feel like Pound has moved into the thirties. Obviously, this was written after the Second World War, but the earlier bits were still well within what we might call high modernism. This is still that, but I feel like I can detect some surrealist influence. The lines feel more loose, more free flowing, more driven by the unconscious. Or maybe it’s just stream of consciousness. But I stand by what I said. It’s evolving into something influenced by surrealists.

A brief reference to Tangiers pulled me up short. Was Pound connected, did he follow, was he friendly to writers like Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs? Also, was this Canto finished when Burroughs and the Beats were making pilgrimages to that North African port city?

A mention of Leviticus XIX and First Thessalonians 4, 11 (the differing nomenclature comes from Pound). The first, Leviticus, is when God instructing Moses in how the Israelites should behave. The second are instructions from Paul. God’s instructions are lengthy and precise, but Paul speaks more generally. And passage 4:11 goes as follows:

And that ye study to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands, as we commanded you;

Is that a reference to what Pound intends to do, post-War, post imprisonment?

Some disparaging, colloquial quotes about Italian generals and the Duke (Il Duce? A Mussolini reference?) indicate… what? Is he mourning the end of Fascist Italy? I think that the quotes, with their lower class tone, are more likely intended to be mocking the speaker than the speaker’s subject.

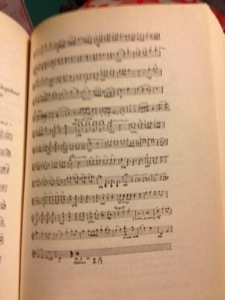

And a lot of references to modern art and writers. Hemingway, I already noted. But also ‘Mr Joyce’ (surely James Joyce) and Manet and Degas…

(made in Ragus) and : what art do you handle?

” The best ” And the moderns? ” Oh, nothing modern

we couldn’t sell anything modern.”

This is a melancholy bit. The whole thing, actually. I can hear Pound adjusting to a new world, one that doesn’t respect… him? The world he loved, he helped created (I am not speaking here of those odious politics, but of how he made literary modernism possible: Eliot, Joyce, Hemingway – all benefitted enormously from his great artistic generosity; maybe be wasn’t the greatest writer of his era, but he made much of it possible).