I was just doing my lonely wandering thing and slipped into that old favorite, Capitol Hill Books, and sort of casually looked for something to spend my store credit on. There were one or two books of poetry (I can’t even remember which ones) and a couple of sci fi/fantasy novels that caught my eye, but not enough to pick up, but rather than keep in the back of my head while I looked for something better.

I was just doing my lonely wandering thing and slipped into that old favorite, Capitol Hill Books, and sort of casually looked for something to spend my store credit on. There were one or two books of poetry (I can’t even remember which ones) and a couple of sci fi/fantasy novels that caught my eye, but not enough to pick up, but rather than keep in the back of my head while I looked for something better.

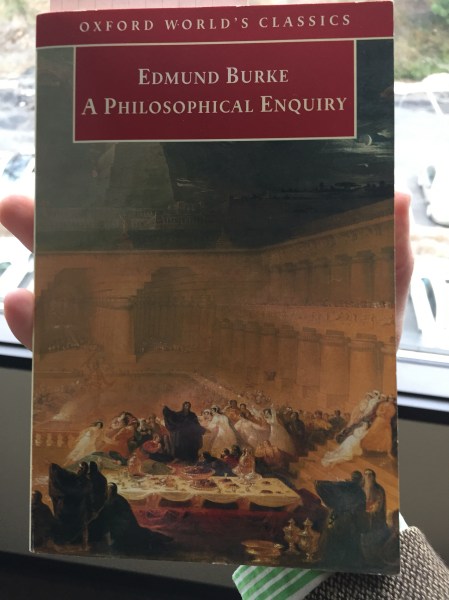

Somehow, while drifting over the philosophy shelves, my eye was caught by a faded Oxford edition whose spine had the inadequate title A Philosophical Inquiry. I picked it up because I figured this had to be an eighteenth or early nineteenth century something or other. Well, you can obviously tell what it turned out to be.

I have a little selection of random Burkean stuff (letters, speeches, essays, and excerpts), but have long been curious about this early and atypical seeming work. I know that he published it as a sort of offering to provide him entry into London’s literary and intellectual society.

I’m simultaneously making my very slow way through the work that Adam Smith considered his magnum opus and lasting claim to fame. Hint: it’s not Wealth of Nations.

Ok, it’s his Theory of Moral Sentiments.

While, having not finished it, I should probably not make too many claims for my understanding of it, but the idea seems to be a combination of a sort of innate (biological? evolutionary?) a priori moral sense that is defined in relation to others, in a natural tendency to seek the moral approbation of others and follow a sort of moral peer pressure.

While not the most interesting bit of Burke’s book, his idea of ‘taste’ strikes me as downright Smithian (Smithite?). In some senses, beauty and appreciation of the aesthetic good is innate, but it is also guided by educated taste makers who help develop a sort of cultural peer pressure, similar to the broader peer pressure Smith seems to stipulate and motivating moral behavior (or moral sentiments, as he would put it in his classic, eighteenth century fashion).

His answer as to the origins of the sublime are surprisingly psychological. The sublime comes from negative emotions. Even though we usually experience the sublime in something beautiful, the source of its sublimity is not its beauty, per se, but it’s connections to pain and fear.

One example is charging bull. A bull quietly chewing cud is not sublime. A bull hitched to a plow and helping till a field is useful, but not sublime. An angry bull charging at you can be sublime, however, because you can be struck by its size (reminding you of your own smallness in the universe) and ferocity and the fear inspired can be sublime.

Part of this is because pain is greater than pleasure, illustrated, he argues by the fact that we will do more to avoid pain than we will the achieve pleasure, which is also why he believe that the sublime must have its origins in pain.

For some reason, this little bit struck me. An example of how the painful end of the spectrum lends itself to the sublime. Also, what an absolutely amazing depiction of Stonehenge. Alone, that passage is worth the price of admission (‘Nay, the rudeness of the work increases this cause of grandeur, as it excludes the idea of art, and contrivance;’).

The word ‘aweful’ appears, a reminder of the actual root of ‘awful,’ which has been reduced from causing a terrible awe to a rather minor nastiness.

At times, Burke seems to take a sort of sadistic glee in the ‘painful’ origins of the sublime, which also helps, stylistically speaking, to compensate for his tendency to engage in something very close to an eighteenth century equivalent to listicles (there are a lot of very short sections, like the one pictured, that can get very repetitive and which do not all seem to add very much to the topic).

At one point, he rather succinctly sums up one of his important premises: For sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones comparatively small…

The association with ‘vastness,’ is really, I would say, an association with (terror or awe inducing) infinite (he uses the term ‘artificial infinite’ to capture this idea), whereas he views beauty as small and precious (in both senses of the word). Because the more powerful sublime has its… not origins, but, to use a term Burke himself uses to describe it, its foundations in pain and fear. Beauty, meanwhile, has its less powerful foundations in pleasure and positive emotions.

He ends with about a dozen pages on words, including poetry. By words, he means a bit of linguistic theory and classical rhetoric. It’s all interesting enough, but he never really explains what it has to do with the sublime nor with the beautiful.

If I can find it, I need to find that old selection of Burke’s writings and try and look for parallels. While I’m sure that this is an outlier in terms of his output – he was a politician and orator, not a philosopher – surely there must be hints of some of his ideas and prejudices underlying his other writings and positions.

Or a replication/re-creation thereof.

Or a replication/re-creation thereof.