Jefferson was a revolutionary, but also, by some modern standards, a conservative (at the risk of seeming to laud George Will, which I am really loathe to do, because he really does not deserve it, he might be the closest comparison).

Until digging into these letters, I hadn’t been aware of how much he was engaged in the discussions around the Constitution. He was in Paris, of course, and I am in now way suggesting he was involved in its writing, which I understand to have been mostly masterminded by James Madison. But he was aware of drafts, of the discussion around later including what we now know as the Bill of Rights, and of the Federalist Papers. He has some recurring concerns around the ability of a President to keep running for office more or less indefinitely, allowing a popular one to become a de facto president for life.

While he talks about the need for limited government, he, like the late Justice Antonin Scalia’s supposed originalism, is not a faithful lover to the idea. In 1788, he writes to Madison about what he thinks an addendum to the Constitution (again, this is about the discussions related to what would be known as the Bill of Rights) ought to include.

In his mind, a ban on monopolies should be one of them. He acknowledges that the prospect of a limited duration monopoly can spur ‘ingenuity,’ but does not believe that to be worth the damage caused by monopolies in general (which, in his wording, I wonder if our modern speech might not interpret what he calls monopolies as patents or copyrights).

He also writes the amendments should include something to ‘abolish standing armies in time of peace…”

He then goes on to say that our militia should be sufficient in to protect us in most cases, since we were not at significant danger from European invasion and our militia ought, he thought, be sufficient to stave off Canadian or Spanish[-American] aggression. Again, he didn’t have much to do with directly writing the Constitution nor the Bill of Rights, except insofar as his ideas were influential, but doesn’t this also seem to suggest that the eventual Second Amendment was not intended to reflect a general acceptance of guns in the population, in general?

Gentle reader, you have no doubt noticed that I am a fool for a new take on Thomas Jefferson, one that dodges standard biography. This one dodges so far as not to be sure what to make of itself.

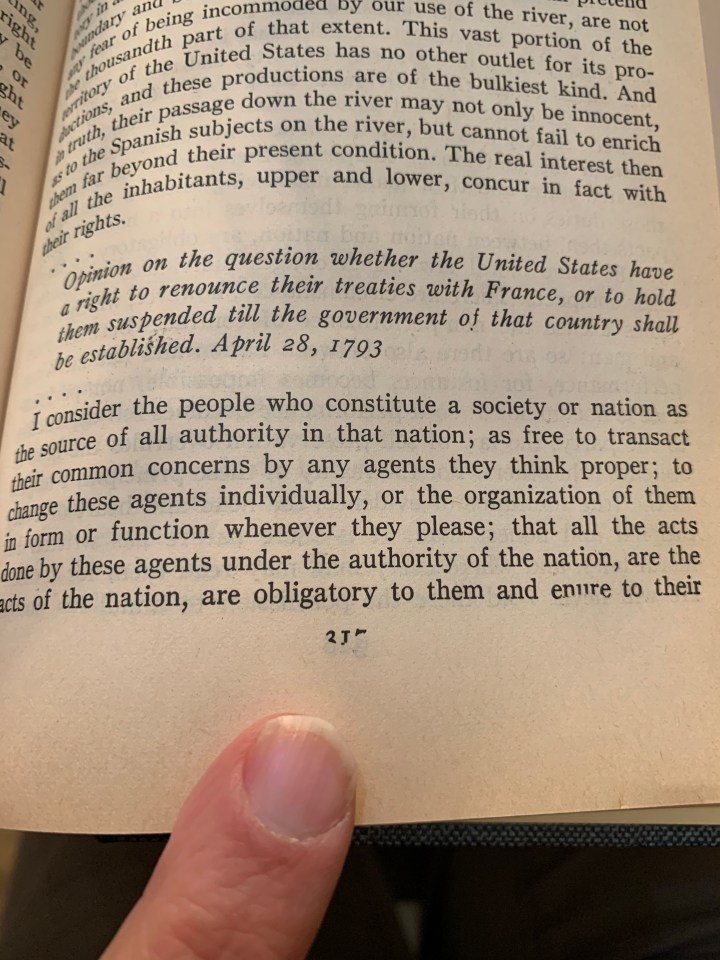

Gentle reader, you have no doubt noticed that I am a fool for a new take on Thomas Jefferson, one that dodges standard biography. This one dodges so far as not to be sure what to make of itself. In an otherwise only marginally interesting answer to the question of whether the United States should renounce its treaties with France until it had established a government. While it’s not clear who needs to establish a government, because both countries had some ups and downs, the date of 1793 suggests it was France that needed to sort itself out.

In an otherwise only marginally interesting answer to the question of whether the United States should renounce its treaties with France until it had established a government. While it’s not clear who needs to establish a government, because both countries had some ups and downs, the date of 1793 suggests it was France that needed to sort itself out.

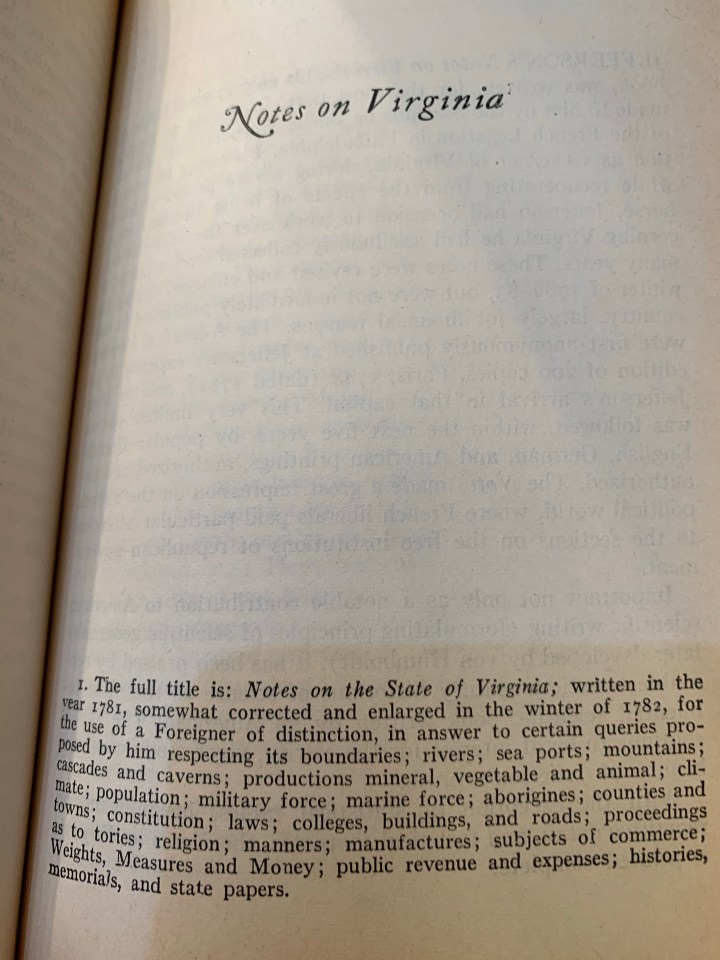

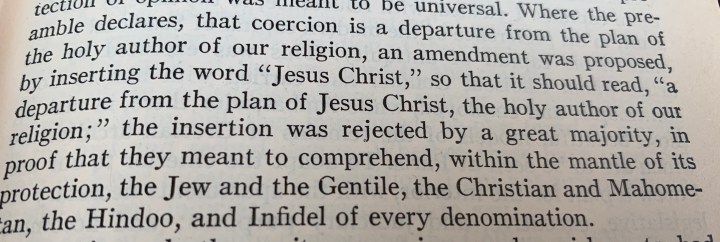

You can see Jefferson’s regular topics and conceits clearly here. A chapter on religion is mainly about the religious freedom he so assiduously (and successfully; he wrote the statute) championed in Virginia. On education, it reflect the inadequacy of both the physical and curricular structure of William & Mary, then the state’s only college; arguments no doubt in support of his quest to establish the University of Virginia at the base of his mountain. You see Jefferson the amateur scientist (and a fascinating digression into some amateur archaeology that he undertook on a Native American burial mound.

You can see Jefferson’s regular topics and conceits clearly here. A chapter on religion is mainly about the religious freedom he so assiduously (and successfully; he wrote the statute) championed in Virginia. On education, it reflect the inadequacy of both the physical and curricular structure of William & Mary, then the state’s only college; arguments no doubt in support of his quest to establish the University of Virginia at the base of his mountain. You see Jefferson the amateur scientist (and a fascinating digression into some amateur archaeology that he undertook on a Native American burial mound.

This slim book, which or may not have been intended for publication, is quite modest and circumspect. He does not speak much of personal matters (alluding obliquely to his wife’s death) but much of legislative comings and goings and you would barely know he was key figure in American history if this was all you had.

This slim book, which or may not have been intended for publication, is quite modest and circumspect. He does not speak much of personal matters (alluding obliquely to his wife’s death) but much of legislative comings and goings and you would barely know he was key figure in American history if this was all you had. Did I need to read another Jefferson book? Probably not. My fifth in the last two years, though the first traditional biography (the others being guided by conceits or else by Christopher Hitchens and so read to understand him rather than Jefferson).

Did I need to read another Jefferson book? Probably not. My fifth in the last two years, though the first traditional biography (the others being guided by conceits or else by Christopher Hitchens and so read to understand him rather than Jefferson).