Emil Petaja asks the reader an important question: what if Finland was populated by secret space wizards?

Yes, that’s right. This book is that bats–t crazy. It starts out like a classic silver age science fiction novel, with a lost spaceman who has survived this cosmic zone of death called the Black Storm. The Storm is growing and it disintegrates everything it touches. Even the crew of the ship that picks up our intrepid spaceman (who is, we will learn later, named Ilmaren) slowly and painfully melts into atomic nothingness just from having been near things that were in or near the Black Storm. He blames himself (as do most people in the first half of the book), but later it is off-handedly said that it couldn’t be him, but maybe his spacesuit was contanimated? Felt like there was some more detail we could have gotten there, but by that time, we are off to the land of the space wizards who descended from the people of modern day Finland. Mostly, they live like gnomish wizards underground, but once a year they come up and party (protected by an illusion, so normies don’t discover them) like it’s approximately 1000 CE.

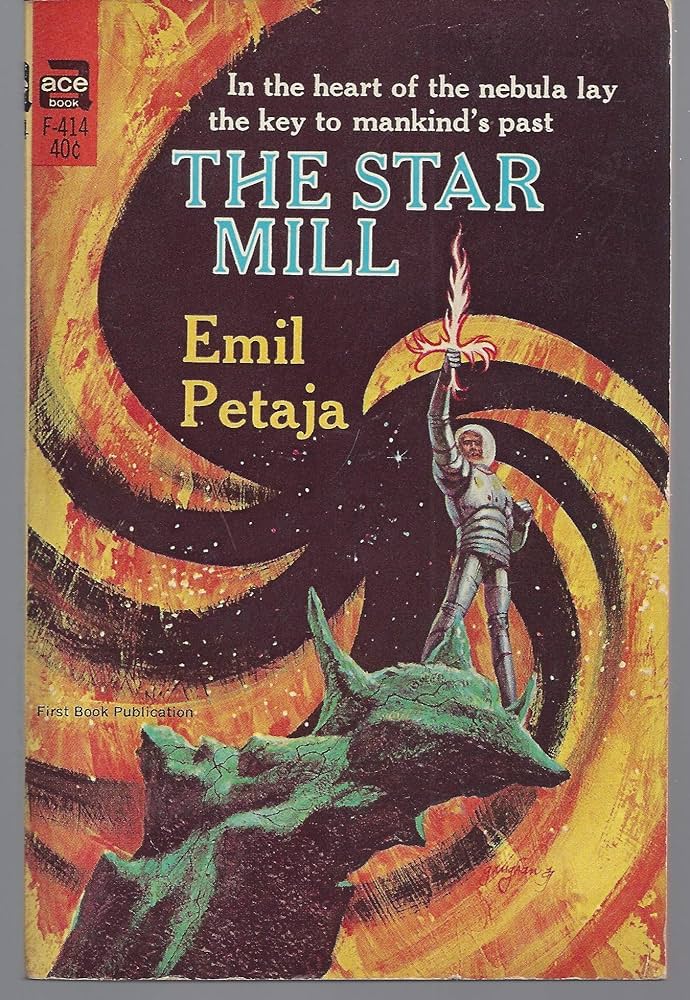

You will be surprised to learn that Ilmaren is actually a chosen savior of the galaxy who must journey to land of goblins, elves, and hell hounds, created by an evil witch who got herself a Star Mill due to… well, it’s a long complicated retelling of Finnish mythology that is barely even metaphor, apparently. Anyway, Ilmaren saves the die by traveling through a tapestry using space magic and destroys the Star Mill (though not the witch! she escapes!) using a science magic… um… light saber, I guess. It’s really not clear. He’s sort of trapped in the little space witch world, but he seemed hopeful, so I guess it’s a happy ending. And we are meant to assume that the Black Storm will not destroy the entire universe anymore, so, job well done.