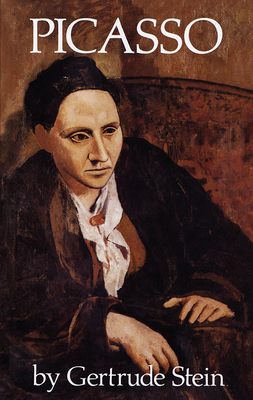

At first it seemed to me that Gertrude Stein was writing like Hemingway. She’s actually writing very specifically like Hemingway did in A Moveable Feast. Especially the bits featuring… Gertrude Stein. Only with more commas (more about that later).

At first it seemed to me that Gertrude Stein was writing like Hemingway. She’s actually writing very specifically like Hemingway did in A Moveable Feast. Especially the bits featuring… Gertrude Stein. Only with more commas (more about that later).

A Moveable Feast is a great read for content, but the writing itself is c–p. We pretend it’s not because we want so much to like it. Sort of like The Old Man and the Sea. When all either of them really are is better than the most execrable of Hemingway’s later work (I’m looking at you, Across the River and Into the Trees).

A friend once told me that Stein’s Making of Americans reads like Henry James, but with two out of three punctuation marks removed and replaced with ‘and.’ Well, Picasso reads like bad Hemingway, but with triple the number of commas and every third comma placed randomly within a sentence. This can make things difficult to understand, as you ask yourself, now, is she creating a new dependent or independent clause that will change the meaning of this sentence or is she just having fun with commas? And if you don’t know what I mean about commas changing the meaning of a sentence, check out the book Eats Shoots and Leaves.

No one in their right mind would read Stein on Picasso in order to understand Picasso. No, you read it in order to read Stein. Just like you don’t read Heidegger on Nietzsche to get anything like a better understanding of Nietzsche.

But… I did get a couple of insights.

She writes very briefly (little more than acknowledgement) of his blue period, but that talks about a slightly later ‘harlequin and rose’ period. She also says this period appeared twice! I had always thought of his clowns appearing in his blue period and don’t know what to make of this claim.

She eschews personal psychology (nothing, for example, about the melancholy of his blue period), but is obsessive about a sort of cultural psychology, with Picasso, in her estimation, being heavily defined by his ‘Spanish-ness.’ But this does lead her to make a remark about the influence of calligraphy on Picasso. You can see something of calligraphy in his ability to create images and complete shapes through a few broad strokes. And, thought she gets some facts and history wrong, she is clearly trying to show the influence of the non-representational religious art and the use of Arabic calligraphy in Muslim Spain.

Finally, and to close on something positive to say, I was pulled up short by one bit. I was dismissive of her attempts to connect his to a certain ‘Russian-ness’ and talk about a Russian period, but then I saw a reproduction of Picasso’s FEMME AU SOURIRE. It wasn’t Russian in the sense that Stein was talking about (or else she completely misreads whatever the Russian character might be), but that 1929 painting really does resemble something from the pre-Stalin, post-Revolution, Russian avant-garde!